I. Issues in Asia and the role of the youth

In 2016, Asia witnessed major events that challenged the region’s perseverance, strength, and resilience.While many economies in the region demonstrated stability both in terms of economics and politics, as evidenced by sustained economic growth and smooth transition of leadership, others were continuously faced with regional security issues, territorial disputes, shifting alliances, resource shortfalls. Amidst these issues, according to Craig Allen (US Ambassador to Brunei Darussalam) as cited by Norjidi (2017), the youth plays a critical role in solving national, regional, and global challenges. Moreover, as mentioned by Allen, such is the case because 65 percent of the population just in the ASEAN region is under the age of 35 comprising 400 million youth and they will define the Asia-Pacific region for decades to come (Norjidi, 2017). Hence, their involvement in addressing pertinent and urgent global challenges such as climate change and sustainable economic growth is vital in the development of the region.

In terms of the establishment of the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC), the ASEAN Secretariat (2012) quoted H.E. Mr. Bagas Hapsoro (Deputy Secretary-General of ASEAN) underscoring that the youth must unite to create a strong network with other youth from different aspects of life in order to forge mutual understanding that will facilitate a boost in regional cooperation in the long run. Moreover, there is also a need to enhance policy advocacy initiatives that would create a robust foundation for the youth’s concerns to be heard by their respective governments and private sector.

Consistent with the AEC’s vision of creating a region that is outward looking, living in peace, stability, and prosperity, bonded together in partnership in dynamic development and in a community of caring societies (Austria, 2004), Hapsoro believed that events that gather the youth of ASEAN are necessary as they provide platforms for information exchange and creativity among them. Likewise, second track diplomacy is vital to which the youth can play a significant role by sharing their inspirations, hopes and feedback towards building a forward-looking ASEAN Community (ASEAN Secretariat, 2012). Clearly, at this point, we need to encourage the active participation of the youth in instigating change to the social-economic-political processes in the region; thus, making their role undeniably essential.

In terms of education, according to the Asian Development Bank [ADB] (2017a), Asia has been a global success story when it comes to educating children. Overall, 90 percent of the children in the region today are enrolled in primary school. For a continent that contained two-thirds of world’s out-of-school children in the 1970s, this has been a swift progress. However, ADB (2017a) furthered that while much progress has been made over the past decade, indicators still point to serious education and human-resource shortfalls at all levels throughout the region, a reality that could dampen Asia’s lofty economic aspirations. To address this, there is a need to expand and diversify the educational sector, particularly of developing economies, by implementing reforms to strengthen governance, and improve education planning, management, and system efficiency (ADB, 2017b). Hence, it is necessary for developing economies to focus on improving synergies between education subsectors, such as: (1) instituting sector-wide policies; (2) harmonizing curricula; (3) ensuring equal access to training programs; and (4) providing flexible pathways for graduates of lower levels to continue their studies at higher levels. As emphasized by ADB (2017b), in many economies, subnational levels of government play an important role in education. Whereas, it is recommended for developing economies to increasingly pursue decentralized approaches to education management, resource allocation, and service delivery – deemed to yield greater inclusiveness and improved education outcomes.

For issues related to employment, one of the aftermaths of the global crises of the 2000s resulted to a global youth unemployment of 74.5 million (a 3.8 million increase from 2007) in 2013 as reported by the International Labor Organization (ILO). This is equivalent to 13.1 percent – almost thrice as high as the adult unemployment rate (Gozun & Rivera, 2017). Similarly, according to Cognac (2012), the recent economic crises has brought the largest ever cohort of unemployed youth because they are three to five times more likely to be unemployed than adults. If this trend will continue, Cognac (2012) predicted that the world would face a 600 million productive job gaps in the next decade. This is even worsened by a still inadequate education and training, skills mismatch, persistent gender gaps, presence of youth in rural and isolated areas, and young people with disabilities. To address this, Cognac (2012) and Gozun and Rivera (2017) call for the need to integrate skills development into broader national development strategies; promote social inclusiveness; focus on school-to-work transitions; enhance partnerships, develop apprenticeship programs, and improve investment climate; support skills and entrepreneurship training and access to finance; focus on local development.

At the regional level, ASEAN cooperation on youth is critical, as emphasized by Hapsoro. The ASEAN Senior Officials on Youth, which is under the ASEAN Ministerial Meeting on Youth, should be assertive and very much active in the implementation of the programs and activities for youth matters. Recognizing the central role of the youth in growth and development, a regional cooperation platform (RCP) for vocational education and teacher training is also critical. That is, RCP members receive support in developing and establishing appropriate platforms for mutual exchange and working formats, such as working groups, conferences, and capacity-building programs for the youth.

Lastly, in the area of tourism, according to the World Travel & Tourism Council [WTTC] (2017), the travel and tourism (T&T) industry employs a higher proportion of women and youth than the entire labor market. In fact, it is a key job creator across the globe, representing 3.4 percent of total employment. Similarly, when including jobs indirectly supported by the industry, T&T creates 1 out of every 11 jobs in the world. In addition, while other sectors like health and education are ahead of T&T in terms of proportion of women employed, T&T employs some of the highest percentages of people between 15 and 25 years old. This is because the T&T thrives on entrepreneurship and as such offers women prospects for self-employment, which are less accessible in other sectors. Its flexible nature, requirement for skilled and unskilled employees, and strong growth prospects also mean that T&T holds real opportunities for job creation to address the youth unemployment problems faced by countries across the world. Of equal importance, the Asian youth has changed the way travelling is done as studied by Lee and King (2015). It was found that the Asian youth (i.e., students in their sample) behave somewhat differently from those in Western settings. Cultural background influenced the travel behaviors of youth as well as their perceptions of a tourism destination. The visiting friends and relatives (VFR) market induced by Asian youth offers greater tourism-related potential than the travel activity than what they undertake on their own.

II. The Asian Barometer Survey

The Asian Barometer Survey (ABS) platform is an online survey conducted by the Dr. Andrew L. Tan Center for Tourism of Asian Institute of Management (AIM) across higher educational institutions (HEIs) in ASEAN Member States (AMS) and East Asia. The ABS data captures the assessment of the attitudes (i.e., awareness, openness, and outlook) and level of preparedness of the youth toward the establishment of the AEC and other important future issues relating to economic policies, social protection, and tourism that resonate with the youth of Asia. Analysis of the data generates timely and relevant insights into what the youth perceive to be the benefits and opportunities that integration poses to them, what negative consequences may arise from increased competition, and how equipped they are for a more integrated Asia.

Over two-thirds of the Asian population is counted among the youth (individuals age 15-30). Hence, much of the development experienced has been fuelled by the steady growth of a skilled, primarily young, workforce, growth of MSMEs, and the accompanying boost in consumer demand (Rivera, 2016). The youth has therefore become the primary focus of the platform because of their increasing critical role in the success of any plans for economic integration, tourism development, and policy formulation. The sampling strategy employed by the platform is a stratified random sampling. Universities in ASEAN and in East Asia were considered and invited to be part of the strata for the youth sample. Then, a random sample of respondents was drawn from each stratum.

The survey was administered through an online portal. It was the preferred method of data gathering over questionnaire booklets in order to: (1) minimize costs, (2) enhance the scope and coverage of the ABS in the future, (3) minimize human error in encoding, (4) guarantee rapid encoding and processing of survey results, and (5) restrict access to the survey and comply with standard statistical protocols. The online survey was conducted in September 2016 with 2,351 respondents.

III. Survey Results

Here are the general findings on the attitudes of youth towards education, employment, and tourism in Asia. Table 1 shows the distribution of respondents from universities in Japan, the Philippines, and Thailand who participated in the survey. Nonetheless, it must be noted that the sample is not restricted to Japanese, Filipinos, and Thais as shown in Table 2. However, increasing the number of respondents from other Asian countries with a variety of nationalities remains to be a challenge.

Table 1. Distribution of sample across strata (universities)

| Strata (HEIs) | Frequency | % | Cumulative |

| Cor Jesu College (Davao, Philippines) | 15 | 0.64 | 0.64 |

| Holy Angel University (Pampanga, Philippines) | 281 | 11.96 | 12.60 |

| Ritsumeikan Asia Pacific University (Beppu, Japan) | 106 | 4.51 | 17.11 |

| Saint Louis University (Baguio, Philippines) | 881 | 37.49 | 54.60 |

| University of San Carlos (Cebu, Philippines) | 776 | 33.02 | 87.62 |

| University of the Thai Chamber of Commerce (Bangkok, Thailand) | 291 | 12.38 | 100.00 |

| TOTAL | 2,350 | 100 |

Table 2. Nationality distribution of youth sample

| Nationality | Frequency | % | Cumulative |

| Cambodia | 1 | 0.04 | 0.043 |

| Indonesia | 19 | 0.81 | 0.85 |

| Lao PDR | 2 | 0.09 | 0.94 |

| Malaysia | 1 | 0.04 | 0.98 |

| Myanmar | 1 | 0.04 | 1.02 |

| Singapore | 1 | 0.04 | 1.06 |

| Thailand | 317 | 13.49 | 14.55 |

| Philippines | 1,924 | 81.87 | 96.43 |

| Viet Nam | 18 | 0.77 | 97.19 |

| Japan | 7 | 0.30 | 97.49 |

| People’s Republic of China | 13 | 0.55 | 98.04 |

| Republic of Korea | 20 | 0.85 | 98.89 |

| Others | 26 | 1.11 | 100.00 |

| TOTAL | 2,350 | 100 |

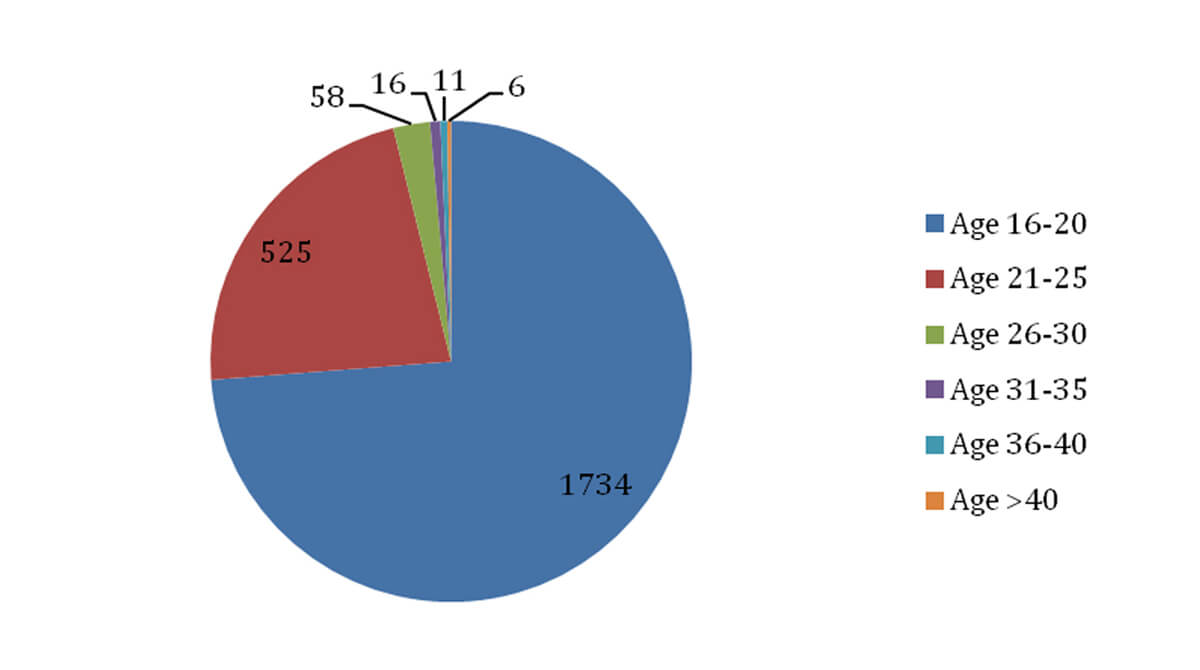

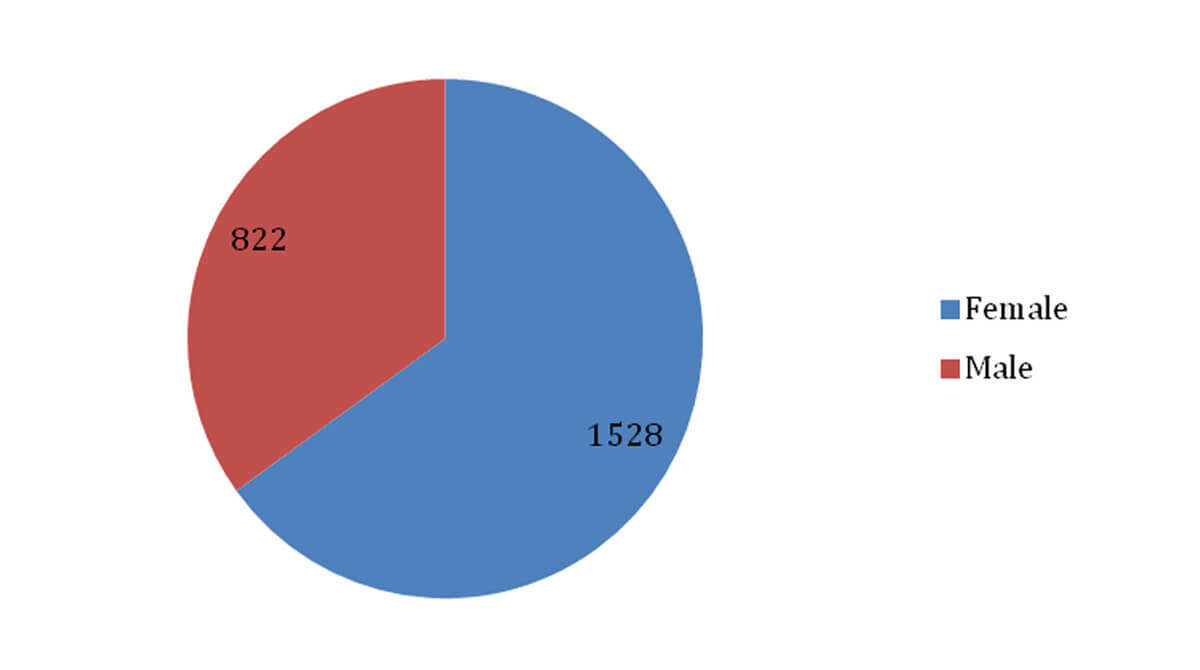

Figure 1 shows the distribution of the respondents who participated according to age group. Since we surveyed Universities, majority belongs to the 16 to 25 age cohorts. Moreover, Figure 2 shows the distribution of the sample according to sex – there are more females than males.

Figure 1. Age distribution of youth sample

Figure 2. Distribution of youth sample according to sex

Meanwhile, Table 3 shows the distribution of the sample according to their level of education at the time the survey was conducted. Of the total respondents, 9.75 percent of them are also taking graduate studies.

Table 3. Level of education distribution of youth sample

| Education | Frequency |

| College (Undergraduate) | 2,350 |

| Master (Graduate) | 254 |

Regarding the general perception of the youth on employment, travel and trading conditions given the AEC, the youth perceives that with regional integration, it will be easier to get a job; will be easier to travel; and trade in and out of Asia will improve as shown in Table 4. On one hand, in terms of the attitude of the youth towards employment opportunities given AEC, Table 5 shows that the youth are optimistic about: (1) finding employment in their home country within a year after graduation, (2) finding employment that is closely related to their degree of specialization in their home country within a year after graduation, and (3) finding employment in another ASEAN country.

Table 4. Perceptions of youth on AEC-employment, travel, and trading

| Perceptions on AEC | Yes | % | No | % | Total |

| Would it be easier to get a job given the ASEAN Economic Community? | 1,999 | 85.06 | 351 | 14.94 | 2,350 |

| Would it be easier to travel given the ASEAN Economic Community? | 2,179 | 92.72 | 171 | 7.28 | 2,350 |

| Do you believe that the ASEAN Economic Community will improve trade in and out of Asia? | 2,262 | 96.26 | 88 | 3.74 | 2,350 |

Table 5. Optimism of youth on AEC in terms of employment

| Questions | Not Optimistic / percent | Optimistic / percent | Very Optimistic / percent | Total |

| How optimistic are you in finding employment in your home country within a year after graduation? | 261 / 11.11% | 1,600 / 68.09% | 489 / 20.81% | 2,350 |

| How optimistic are you in finding employment that is closely related to your degree of specialization in your home country within a year after graduation? | 231 / 9.83% | 1,580 / 67.23% | 539 / 22.94% | 2,350 |

| How optimistic are you in finding employment in a non-Asean country within a year after graduation? | 474 / 20.17% | 1,446 / 61.53% | 430 / 18.30% | 2,350 |

| How optimistic are you in finding employment in another Asean country within a year after graduation? | 311 / 13.23% | 1,558 / 66.30% | 481 / 20.47% | 2,350 |

| How optimistic are you in finding employment that is closely related to your degree of specialization in a non-Asean country within a year after graduation? | 483 / 20.55% | 1,483 / 63.11% | 384 / 16.34% | 2,350 |

On the other hand, in terms of the youth’s willingness to take employment opportunities given AEC, Table 6 shows that they are willing to: (1) take a job in another ASEAN country that is not related to their degree of specialization, (2) to take a job in their home country that is not related to their degree of specialization, and (3) to take a job in a non-ASEAN country that is not related to their degree of specialization in a non-ASEAN country within a year after graduation.

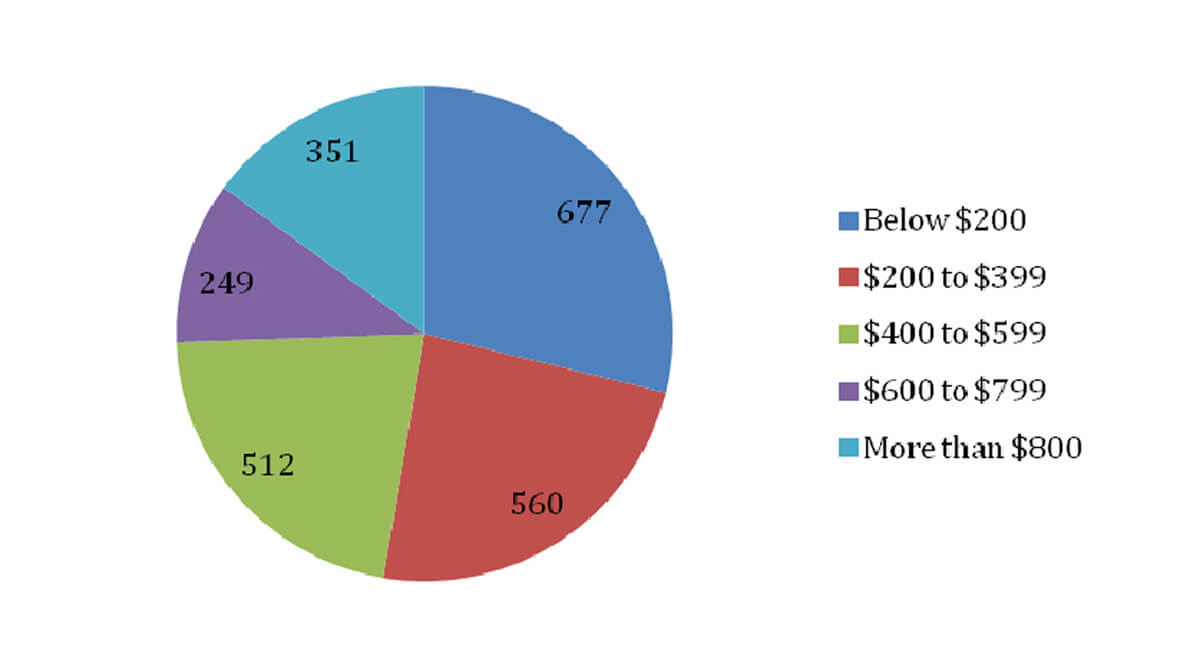

In tracing the attitudes of the youth toward travel and tourism, Figure 4 shows that majority has a travel budget of below USD 200.00 but Figure 5 shows that the youth prefers to stay in a destination for more than four (4) days. It must be the case that the youth often travel in groups thereby sharing the cost with others.

Table 6. Willingness of youth on AEC in terms of employment

| Questions | Not

Willing / Percent |

Willing / Percent | Very

Willing /Percent |

Total |

| How willing are you to take a job in another Asean country that is not related to your degree of specialization? | 587 / 24.98% | 1,335 / 56.81% | 428 / 18.21% | 2,350 |

| How willing are you to take a job in your home country that is not related to your degree of specialization? | 712 / 30.30% | 1,321 / 56.21% | 317 / 13.49% | 2,350 |

| How willing are you to take a job in a non-Asean country that is not related to your degree of specialization? | 679 / 28.89% | 1,302 / 55.40% | 369 / 15.70% | 2,350 |

Figure 3. Travel budget of youth sample

With regards to the respondents’ self rated awareness on the tourism slogans of AMS, it can be seen from Table 7 that for countries that have established tourism industries (i.e., Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand), majority of the respondents were aware of their slogans and they also find it appealing. On the other hand, for countries that have emerging tourism industries (i.e., Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Myanmar), majority of the respondents were not aware of their slogans. Perhaps, they are aware of the destination but not necessarily the country slogan. This calls for a more intensive promotional strategy to enhance not only familiarity about the destination but also about the country as represented by the slogan.

Figure 5. Length of stay of youth sample

| Tourism Slogans | Not Aware /Percent | Aware but not appealing /Percent | Aware and appealing /Percent | Aware and very appealing /Percent | Total |

| Brunei Darussalam:

“A Kingdom of Unexpected Treasure” |

1,159 /49.32% | 531/22.60% | 553 /23.53% | 107/4.55% | 2,350 |

| Cambodia:

“Kingdom of Wonder” |

944/40.17% | 553/23.53% | 748/31.83% | 105/4.47% | 2,350 |

| Indonesia:

“Wonderful Indonesia” |

722/30.72% | 670/28.51% | 810/34.47% | 148/6.30% | 2,350 |

| Lao PDR:

“Simply Beautiful” |

1,075/45.74% | 562/23.91% | 615/26.17% | 98/4.17% | 2,350 |

| Malaysia:

“Malaysia Truly Asia” |

473/20.13% | 553/23.53% | 942/40.09% | 382/16.26% | 2,350 |

| Myanmar:

“Myanmar Let the Journey Begin” |

932/39.66% | 619/26.34% | 678/28.85% | 121/ 5.15% | 2,350 |

| Philippines:

“It’s More Fun in the Philippines” |

196/8.34% | 326/13.87% | 729/31.02% | 1,099/46.77% | 2,350 |

| Singapore:

“Your Singapore” |

523/22.26% | 456/9.40% | 859/36.55% | 512/21.79% | 2,350 |

| Thailand:

“Amazing Thailand” |

504/21.45% | 481/20.47% | 851/36.21% | 514/21.87% | 2,350 |

| Viet Nam:

“Vietnam Timeless Charm” |

768/32.68% | 570/24.26% | 793/33.74% | 219/9.32% | 2,350 |

III. Conclusion

The ABS continues to evaluate the attitudes of the youth among AMS by which regional integration could impact on their lifestyle, expectations, and movements (intra- and extra-ASEAN), employment opportunities (domestic, within the ASEAN, outside of the ASEAN), and travel behavior.

Descriptive statistics showed that the youth is optimistic of the effects of regional integration. Moreover, it can also be construed from the results that there is a need to intensify country promotions to increase awareness. Furthermore, just like in the first round of the ABS, there is still a need to expand information about pertinent issues (i.e., regional integration, employment, and travel) particularly on its respective implications on youth welfare. As such, the discussion of these issues should not be limited on economic leaders and policymakers. It should also include the youth to give them the opportunity to take part in the region-wide economic activities that will address issues concerning them.

- References

ASEAN Secretariat. (2012, March 08). Youth play an important role in realizing ASEAN community.

Retrieved from http://asean.org/youth-play-an-important-role-in-realising-asean-community/

Asian Development Bank (ADB). (2017a). Education issues in Asia and the Pacific. Retrieved from

https://www.adb.org/sectors/education/issues

____. (2017b) Education reform. Retrieved from https://www.adb.org/sectors/education/issues/reform

Austria, M.S. (2004). Strategies towards an ASEAN Economic Community. CBERD Working Paper Series

(2004-02). Retrieved from http://www.dlsu.edu.ph/research/centers/cberd/pdf/papers/Working%20Paper%202004-02.pdf

Cognac, M. (2012, March 12). Youth employment in ASEAN. Retrieved from http://www.social-protection.org/gimi/gess/RessourceDownload.action?ressource.ressourceId=29409

Gozun, B.C., & Rivera, J.P.R. (2017). Role of education in encouraging youth employment and

entrepreneurship. DLSU Business & Economics Review, 26(3).

Lee, C.F., & King, B. (2016). International students in Asia: Travel behaviors and destination perceptions.

Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 21(4), 457-476.

Norjidi, D., (2017, February 26). ASEAN youth role crucial in meeting challenges. Borneo Bulletin.

Retrieved from http://borneobulletin.com.bn/asean-youth-role-crucial-meeting-challenges/

Rivera, J.P.R. (2016, January). Understanding youth perception on the ASEAN Economic Community: The Philippine case. AIM Leader, 32-35.

World Travel & Tourism Council (WTTC). (2017). Gender equality and youth employment in travel &

tourism. Retrieved from https://www.wttc.org/-/media/files/reports/policy-research/gender_equality_and_youth_employment_final.pdf

Authors:

John Paolo R. Rivera is the Associate Director; and Eylla Laire M. Gutierrez is the Research Associate of the AIM-Dr. Andrew L. Tan Center for Tourism.